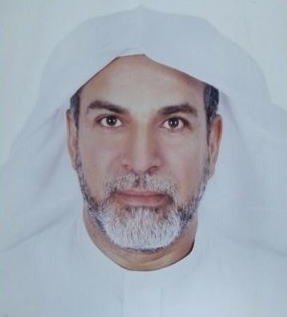

Sheikh Samir al-Hilal (born 20 December 1960) has been isolated from the outside world since December 2015, raising serious concerns that he may be suffering from torture and other forms of cruel and degrading treatment in Saudi prisons. On 16 December 2015, Ministry of Interior forces arrested al-Hilal as he was leaving his home in the al-Anoud residential neighborhood in the eastern city of Dammam.

Following his arrest, Saudi forces immediately detained him in their car in front of his house and then entered his home – brandishing their automatic weapons in his wife’s face and confining her and her infant to one of the rooms – and immediately searched the house for more than an hour and a half. They did not present a warrant authorizing them to search the house, in clear violation of Article 41 of the Code of Criminal Procedure: “Persons, their dwellings, offices, and vehicles shall be inviolable.”

Sheikh al-Hilal was not wanted prior to his arrest, and security forces did not produce an arrest warrant. After his arrest, he was not allowed to contact his family for seven months. His father was able to call him by phone, although no one was allowed to visit him until August 2019. Saudi Arabia also deprived Sheikh al-Hilal of his fundamental right to a lawyer, even though these arbitrary measures violate Article 119 of the aforementioned code: “In all cases, the investigator may order that the accused not communicate with any other prisoner or detainee, and that he not be visited by anyone for a period not exceeding sixty days if the interest of the investigation so requires, without prejudice to the right of the accused to communicate with his representative or attorney.”

Al-Hilal’s family was unable to learn the location of his detention for a period of time, and when they contacted the Dammam Prison administration, they were told that he was in al-Ha’ir Prison in Riyadh, the country’s largest political prison. After the family consulted the prison, the custodians confirmed his presence there. In July 2016, one of Sheikh al-Hilal’s wives was contacted and notified that he could be visited; however, after his family went to the prison to visit him, they were prevented from entering on the basis that the request was specific to the victim’s wives only.

Sheikh al-Hilal’s wives tried to visit him again, but the custodians did not allow them to do so, explaining that he would not be able to communicate with anyone because he did not cooperate with them during the investigation. Mabahith interrogators often use the term “lack of cooperation during interrogation” when a detainee refrains from certifying statements prepared for him by them, refuses to make specific confessions, or refuses to spy on prisoners or slander activists and opinion holders.

The family sent many letters to official entities to enable them to visit Sheikh Samir al-Hilal, including the emarah of the Eastern region, the Mabahith in Dammam, al-Ha’ir Prison in Riyadh, as well as the Bureau of Investigation and Prosecution in Riyadh, the Ministry of Interior, and the National Security Center in Riyadh.

After Sheikh al-Hilal’s family contacted the official human rights body in Riyadh, it informed the family that it had visited the victim twice, in May 2016 and February 2017, and explained that it had submitted a letter to the Ministry of Interior containing a series of requests, including allowing visits and contact with the victim.

In addition to the arbitrary detention of Sheikh al-Hilal and the denial of his basic rights, such as his right to communicate with the outside world, retain a lawyer, and receive the indictment against him, the Saudi government pressured his family, summoning his wives for interrogation on more than one occasion.

In October 2016, one of Sheikh al-Hilal’s wives received a call informing her that someone needed to meet with an officer at the Dammam Mabahith. When a relative of the victim went, they told him they had an order to search al-Hilal’s house. Afterwards, a group of Ministry of Interior officers searched the house and confiscated SAR 58,000 belonging to the victim’s wife. The confiscated sum was not returned to the wife until August 2019. In April 2017, the victim’s wives were again summoned for interrogation at Dammam’s general prison. Although he has been in detention for 43 months since his arrest, Sheikh al-Hilal is still denied his fundamental right to contact his family and retain a lawyer, in clear contempt of Article 4 of the Code of Criminal Procedure: “Any accused person shall have the right to seek the assistance of a lawyer or a representative to defend him during the investigation and trial stages.”

Likewise, he has not been brought before a court or received the indictment, in clear violation of Article 114 of the aforementioned law: “The detention shall end with the passage of five days, unless the investigator sees fit to extend the detention period. In that case, he shall, prior to expiry of that period, refer the file to the Chairman of the Bureau of Investigation and Prosecution branch, or the deputy head of the internal departments within his jurisdiction, so that he may issue an order to release the accused or extend the period of detention for a period or successive periods provided that they do not exceed, in total, forty days from the date of arrest. In cases that require detention for a longer period, the matter shall be referred to the Director of the Bureau of Investigation and Prosecution, or his delegated deputy, to issue an order to extend for a period or successive periods, none of which shall exceed thirty days, and their total shall not exceed 180 days from the date of arrest of the accused.

Thereafter, the accused shall be directly transferred to the competent court, or shall be released.” Also, “in exceptional cases requiring a longer period of detention, the Court may approve the request for an extension of the detention for a period or successive periods at its discretion and shall issue a warrant.”

The ESOHR believes that the Saudi government is in deep violation of its domestic laws by continuing to detain Sheikh al-Hilal. The ESOHR notes that his arrest is considered “arbitrary” according to international standards observed by the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, in particular Article 9 of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, which says, “No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention or exile,” as well as Article 9 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which says, “Anyone arrested or detained on a criminal charge shall be brought promptly before a judge or other officer authorized by law to exercise judicial power and shall be entitled to trial within a reasonable time or to release.”