The body of journalist Jamal Khashoggi – whom Saudi Arabia has acknowledged was killed in its consulate in Turkey after he entered it on October 2, 2018 – may be added to a long list of bodies detained by the Saudi government.

During different periods of its rule, the Saudi government has adopted the practice of detaining the bodies of victims of torture and extrajudicial killings or has taken arbitrary measures. Since January 2016, it has systematically and conspicuously resumed the detention of many victims, concealing their fate from their families. This behavior, which is contrary to international law and the teachings of Islam from which Saudi Arabia claims to derive its system, has left the families of the victims in endless and inescapable psychological torment.

Saudi Arabia has not responded to the many appeals and demands calling on it to stop or reduce the death penalty, but its disgraceful behavior in failing to release corpses has made clear Saudi Arabia’s deep disregard for human and legal boundaries and has exposed a deeper level of persecution of the people. This is in complete opposition to what Saudi Arabia should be doing to halt the violation of the right to life.

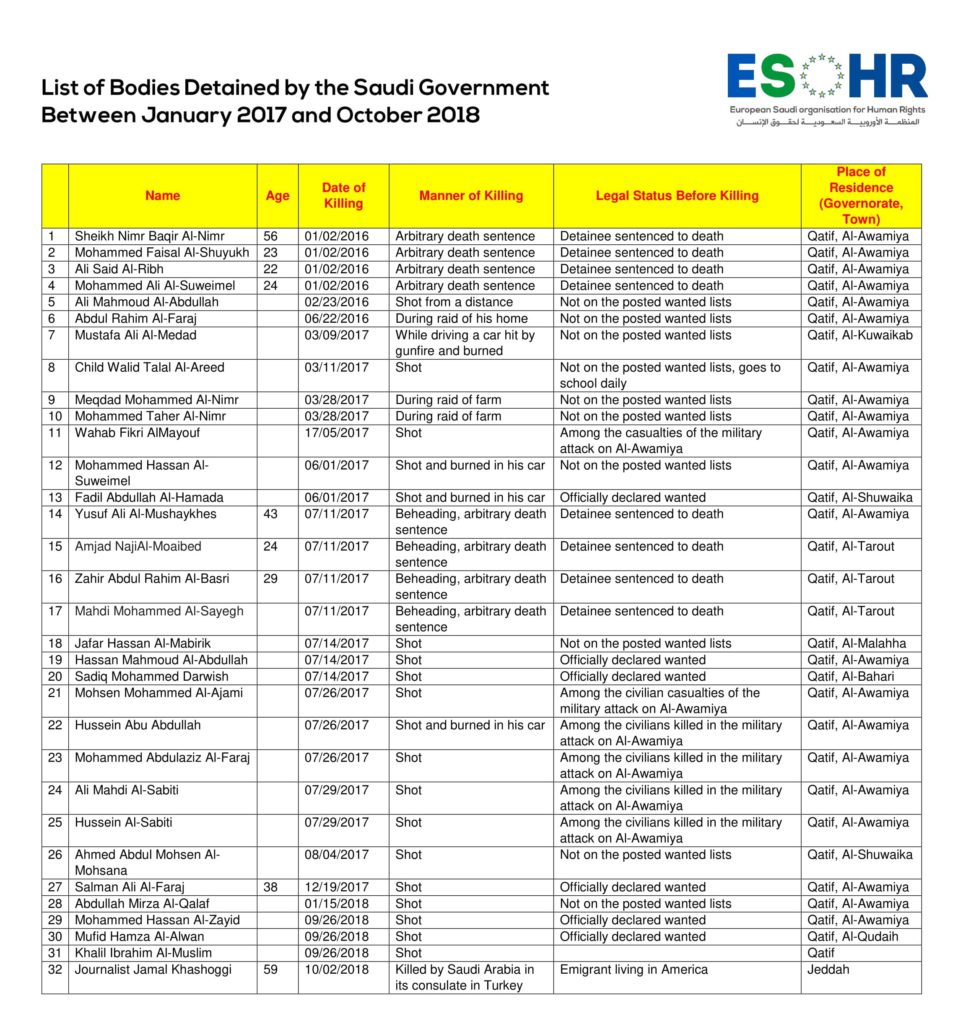

As of October 2018, the number of corpses held by Saudi Arabia and demanded by their families, has reached 32 bodies killed in various ways.

Sentenced to death:

Saudi Arabia has carried out the death penalty against people who exercised peaceful freedom of expression, reflecting its willingness to disregard dissenters’ right to life whenever it wants. On January 2, 2016, the Saudi government carried out a mass execution of 47 people, including social justice activist Sheikh Nimr Al-Nimr, as well as children Mustafa Abker, Meshaal Al-Faraj, and Abdul Aziz Al-Ghamdi, child demonstrator Ali Al-Ribh, and demonstrator Mohammed Al-Shuyukh.

Also executed was Mohammed Al-Suweimel, who was not charged with killing or bloodshed, along with the mentally handicapped Abdul Aziz Al-Taweeli.

Not only did the Saudi government carry out these unjust sentences and ignore all international criticism and accountability, it also completed a series of violations and crimes by detaining some of the bodies.

The European Saudi Organisation for Human Rights Organization (ESOHR) has identified and confirmed that a number of victims whom Saudi Arabia publicly admits to killing have not been handed over to the families, despite their demands.

After the executions, some families issued statements demanding the handover of the bodies of their loved ones for burial according to their wishes or directives. Some families also submitted various claims to the official authorities.

In July 2017, the Saudi government carried out another death penalty against victims sentenced to death after a trial that largely lacked the most basic conditions for fair trials. Its victims were Yousef Al-Mushaykhes, Amjad Al-Moaibad, Zaher Al-Basri, and Mahdi Al-Sayegh. The charges against them included the exercise of freedom of expression and demonstration, along with other charges including use of violence without any concrete evidence other than confessions under torture and coercion. None of the charges were classified as serious crimes. After the families learned of the executions through the media, they published a statement calling for“the bodies to be turned over.”

Extrajudicial killing:

Since 2011, the Saudi government has used excessive violence against rights-seekers after their participation in demonstrations demanding political freedoms, civil rights, and the release of detainees. The increase in excessive violence, as well as persecution, abuse,and the crushing of dignity through torture and humiliating and degrading treatment, have led to counter-violence among some. Between October 2011 and August 2018, the government, in the context of its use of excessive violence and arbitrary measures, killed at least 83 people in Qatif alone in a variety of ways, including torture and arbitrary executions, street assassinations, incineration, raids, and prison killings that cannot be investigated because of the lack of judicial independence.

After the mass execution in January 2016, Saudi Arabia has clearly renewed its practice of the bodies of holding on to the bodies of victims of excessive violence and summary or arbitrary killing. With the case of journalist Jamal Khashoggi– whom Saudi Arabia acknowledged on October 19, 2018, was killed in its consulate by its own agents and has yet to offer any official indications so far about the fate of his body– the number of detained bodies totals 32, including the child, Walid Al-Areed, who was killed by government forces and then claimed by official media to be a wanted terrorist.

Justifications of the Saudi government:

Most families of citizens killed by government forces submit letters to official authorities, such as the official Commission on Human Rights, the Ministry of Interior, and the Emarah of Eastern Province, in which they demand the handover of the bodies of their relatives for burial according to their religious beliefs and wishes. Some families have resorted to issuing public statements repeating the same demands, but they have all been refused or ignored.

According to the family of Sheikh Nimr Al-Nimr, the Saudi government responded that it would not turn over his body, explaining that he had been buried in a cemetery for “Muslims,” at a time when Shiites are portrayed in many educational books and elsewhere, printed at the expense of the government, as“polytheists and infidels.” Regarding two victims, Mohammed Taher Al-Nimr and Meqdad Mohammed Al-Nimr, a secret police official said, in response to the request for the return of the bodies, that the Ministry of Interior – before the transfer of its powers to the Presidency of State Security – issued a decision to prohibit the handover of the bodies. Similarly, the request of the family of Abdul Rahim Al-Faraj was rejected by the office of the governor of the Eastern Province, who said that the decision was issued by Riyadh not to hand over the body to the family.

The refusal of official Saudi authorities to hand over the bodies to the families has many inconsistencies. Some sources close to the families indicated that the government justified holding on to the bodies because the victim was previously present on the wanted lists; however, at least 15 of the 32 victims were not on the wanted lists according to the organization’s tracking.

In addition, there are no specific laws on the issue of handing over bodies to families. An official newspaper quoted responsible sources in the General Court as saying that when the court issues a death sentence for any offender, the court has nothing to do with the date or manner of execution or the handing over of the bodies of the condemned to their families. These sources added that handing over or not handing over the bodies occurs“outside the jurisdiction of the court and is in accordance with the instructions communicated to the competent authorities in accordance with the public interest.”In other words, the judiciary is dominated by the king and the influential around himand cannot intervene in these violations.

Violations of international law:

According to international human rights law, the Saudi government’s failure to release corpses is a clear violation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child, signed by Saudi Arabia,as well as other treaties and laws.

The Commission on Human Rights says in paragraph 11.10 of its resolution (CCPR/C/106/D/2120/2011) published in November 2012, which relates to one of the cases it considered involving the failure of a government to inform of the time of execution, release the body, and disclose the burial site: “The Committee understands the continued anguish and mental stress caused to the authors, as the mother and sister of the condemned prisoner, by the persisting uncertainty of the circumstances that led to his execution, as well as the location of his grave. The complete secrecy surrounding the date of the execution and the place of burial, as well as the refusal to hand over the body for burial in accordance with the religious beliefs and practices of the executed prisoner’s family have the effect of intimidating or punishing the family by intentionally leaving it in a state of uncertainty and mental distress. The Committee therefore concludes that these elements, cumulatively, and the State party’s subsequent persistent failure to notify the authors of the location of Mr. [name redacted]’s grave, amount to inhuman treatment of the authors, in violation of article 7 of the Covenant.”

In addition, in paragraph 27 of the report (E/CN.4/2006/53/Add.3) submitted to the Commission on Human Rights in March 2006, the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial executions stated: “For the prisoner and for his or her family or family, the other issue is that a lack of transparency in what is already a harrowing experience– waiting for one’s execution – can result in ‘inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.’”

Among the victims whose bodies have been detained or disappeared are those who have left behind children, including infants, such as Sheikh Nimr Al-Nimr, Yusuf Al-Mushaykhes, Mohsen Al-Ajami, Ali Al-Sabiti, Salman Al-Faraj, and journalist Jamal Khashoggi. The Saudi government has also violated the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which it ratified, which stipulates in Article 9, Paragraph 4, that in cases where one or both parents or the child were subjected to detention, imprisonment, exile, deportation, or death (including death caused for any reason during the person’s detention by the state)that “State party shall, upon request, provide the parents, the child, or, if appropriate, another member of the family with the essential information concerning the whereabouts of the absent member(s).”

According to what is being circulated by activists, and which the Saudi government has not acknowledged to date, there are reports of the death or killing of Sheikh Suleiman Al-Dawish, detained since April 22, 2016, after his criticism of Mohammed bin Salman, as well as of the death or killing of Sheikh Safar Al-Hawali, detained since July 2018. If confirmed, these reports will increase the number of bodies detained to 34.

The ESOHR believes that the 32 bodies are unjustly held by the Saudi government in contravention of international laws and considers their detention to be violations against the victims, whether they were killed through arbitrary judicial procedures or by extrajudicial violence and killing. Furthermore, their detention constitutes psychological trauma for the families.

The Saudi government is required to hand over to the families all bodies that remain in its custody and end the psychological torture suffered by the families by meeting their right to bury their loved ones according to their wishes or the instructions of the victims. The ESOHR also stresses that their killing by such methods calls for investigating and holding accountable all those responsible for extrajudicial killings or for unfair trials.